|

|

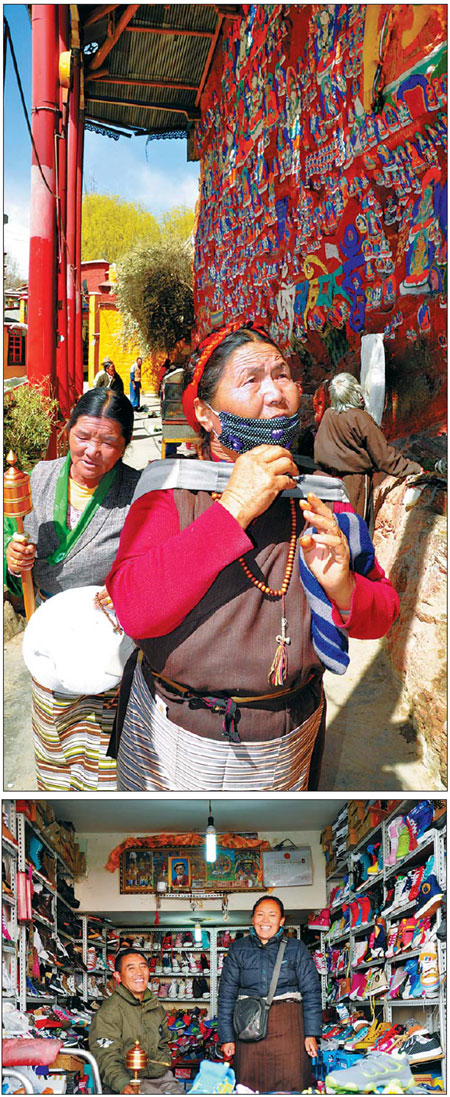

From top: Tsesum has her daily prayer walk in Lhasa. Tsesum's son Qambaphuntsog and his wife at their shoe store. Photos by Liu Xiangrui / China Daily |

Related: A happy city

Lhasa's residents are enjoying a transformation in life quality. Liu Xiangrui and Dachiong report in Lhasa.

Tsesum recites her mantras in low tones and prostrates herself in prayer in front of a rock wall packed with colorful Buddhas. She touches her head to the ground in devotion every time she prays. The 66-year-old resident of the Tibet autonomous region's capital Lhasa says Tibet's transformation and her family's improved lot have changed the way she prays. "I'm grateful life's changing for the better, day by day," she says. "The blissful light of Buddha shines on us now. All I pray for now is a warm and happy family and a peaceful society." Tsesum first joined the throngs of Tibetans who prostrate themselves and spin prayer wheels 15 years ago. She spends about four hours walking from the early morning and spends about three more hours resting in teahouses and parks.

"The prayer walk is a mirror," she explains.

"I have more free time than before, when we were struggling to survive. No pilgrim skips sweet tea. We all enjoy relaxing now."

Lhasa's teahouses are packed with the devout, so Tsesum knows she'll likely run into friends.

Tsesum often meets Lhagpatsering in the teahouse. The 59-year-old retired carpenter, who receives a monthly pension of 1,300 yuan ($206), says he's planning a pilgrimage with his wife to temples in Qinghai province and to Mount Wutai in Shanxi province this year.

His wife is retired from a carpet factory and receives a pension of more than 2,000 yuan a month.

The only obstacle to their journey is Lhagpatsering's work on the neighborhood committee. He was the only member until recently.

"I'm glad I have got a colleague and can take a break," he says.

Lhagpatsering says he's impressed by the growing connections between Tibet and other parts of China.

His 24-year-old daughter Tsedron, a village official in eastern Lhasa, took a 5-year-old boy from the village to Sichuan province's capital Chengdu in late March to seek treatment for his degenerative brain disease.

The county government also provided a 50,000-yuan subsidy to the boy's cash-strapped family.

"It was unimaginable in the past," Lhagpatsering says.

He recalls how transportation and financial burdens prevented Tibet's rural residents from seeing a doctor - let alone seeking medical treatment in faraway hospitals.

"Our lives and transportation have improved," he says.

Lhagpatsering says he might take a plane or train for his pilgrimage. He recalls the seven unforgettable months he spent in Beijing in 1992 - the only time he left Tibet.

"Visiting Beijing was a distant dream for many then," he says.

He was among a group of traditional carpenters flown in to work on a replica of Lhasa's Johkang Temple in Beijing's Chinese Ethnic Culture Park.

He wishes to revisit Beijing and the replica he created decades ago.

Zhabsang talks about her family as she sits in the teahouse, spinning a prayer wheel.

"Now, I have nothing to worry about," the 58-year-old says.

"Both my kids have good jobs."

Zhabsang grew up illiterate in rural Tibet and came to the region's capital after marrying.

Her elder daughter runs a shop with her husband.

Zhabsang is especially proud of her younger 28-year-old, who graduated from Tibet University and now works in a county in Xigaze.

"She didn't let us down," Zhabsang says.

The mother is self-congratulatory about supporting her daughter despite hardships.

Zhabsang's husband, who is a manual worker, used to have limited income. The couple placed their all their hope on their younger daughter. Their situation is better now, because her husband's earnings have significantly increased.

"My daughter suggested her father quit his job anytime he wants, and she'd support us," Zhabsang says.

Several neighbors' children are college students, too, Zhabsang says.

"Young people receive better education nowadays. That gets them more satisfying jobs and brighter futures."

There are about 13,000 college graduates among the 3 million Tibetans in 2012, the autonomous region government's human resources department reports.

Tsesum sips on milk tea after returning from her pilgrimage to her apartment, where her family of four lives in three small rooms.

The local government provided the flat in the 1980s at the cost of 200 yuan a year.

The living room's walls and ceiling are covered with intricate traditional paintings, created by her son, who makes his living as a decorator.

He also put wooden flooring in all the rooms, which alleviates Tsesum's arthritis.

"It wouldn't be considered anything special for a well-off family," Tsesum says.

"But he did all the work himself."

She says he shows filial love through deeds.

Tsesum often tells her children about her childhood.

Her family lived as serfs serving the "big three" estate holders - bureaucrats, aristocrats and high-ranking monks - near the Potala Palace before Tibet's 1959 democratic reforms.

"Authorities had a name list," she recalls.

"We were forbidden to walk around freely - not to mention take prayer walks. We patched even the shabbiest clothes again and again. We had hungry days and, needless to say, the food always tasted terrible. We still had to eat it to survive."

Tsesum says she's proud to be part of Lhasa's growth. She helped build the city - literally, as she started working in construction at age 18 and helped complete Lhasa's airport in the 1960s.

"We didn't have machines, so we carried giant rocks on our backs," she recalls.

"But I worked so happily. I was young and not afraid of hard labor. It felt good to contribute to the construction of a new society as a free citizen."

Tsesum met her husband at the construction site, where he also worked. She has lived with her eldest son, Qambaphuntsog - one of her four children - since her husband passed away several years ago.

The 43-year-old rents a shop selling shoes. The approximately 3,000 yuan it brings in a month is the family's main income source.

"Certainly, many people in Lhasa are richer than us, but I'm content," Tsesum says.

"At least my family has the basics, even if we don't have the best."

Tsesum says she hopes her family has already overcome its hardest times. She recalls crying every day when Qambaphuntsog's wife died of cancer seven years ago.

"She was very kind," Tsesum says.

"We couldn't just let her die, while we had to feed the family, too."

Neighbors and the local government helped when the treatments plunged the family into debt.

Qambaphuntsog has since turned the shoe stall into a store and plans to expand again. Tsesum has applied for interest-free loans from a local women's federation.

"We'll upgrade our products for better deals, too, because people's demands are becoming more sophisticated," Qambaphuntsog says.

Tsesum says she believes her family can repay the loans and is preparing to buy a larger apartment in a few years, as long as their business runs smoothly.

Tsesum is grateful for her warm family and that her son's new wife treats her "like her own mother", she says.

Her granddaughter in high school brings joy and hope to the family, she says.

"She is thoughtful and studies hard," Tsesum says.

The family hopes to save for her college.

The girl says: "I want to attend college in an inland city to enrich my experience and expand my horizons."

Tsesum shares her hopes, while appreciating that life's never been better.

"We're enjoying life," she says. "It's not just me. All the pilgrims agree."

Contact the writers through [email protected].