Cutting through myth of ancient art

|

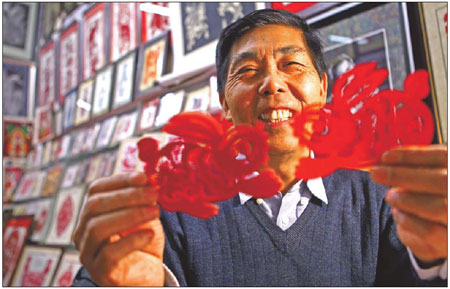

Paper cutting master Xu Yang holds a pair of leaping rabbits he cut for the Year of the Rabbit. The 62-year-old believes the charm of this traditional art lies in the fact it grasps the soul of an object, not simply imitates its appearance. [Photo/China Daily]

|

In Xu Yang's eyes, however, that kind of paper cutting simply yields to commercial demand and has nothing to do with the real art.

"The public's biggest misunderstanding about paper cutting is that the works and the prototype have to be very much alike," said the 62-year-old, who has been practicing the craft for more than three decades.

Dating back more than 2,600 years ago, traditional Chinese paper-cut artworks were never meant to be realistic, the abstract nature of the art means it has more to do with a craftsman's heart than with realistic images, said Xu.

He said the different patterns, such as crescents, willow leafs and serrated shapes can convey all kinds of messages.

"Likeness is not the final goal in the art of paper cutting," he said.

One of his favorite works is called Universal Celebration, which shows the scene of Chinese farmers celebrating during a festival. The figures in the work are either doing the yangge dance with colored ribbons and waist-drums or doing the lion dance, yet all are impossibly proportioned and have a strange appearance and exaggerated gestures.

"They are nothing like real people, but you can feel the strong happiness conveyed by their expressions and gestures," said Xu. "Chinese folk art has its unique charm despite being unrefined and rustic. It's more vivid and interesting, and has a note of real life, which is easier to taste compared with tasteful art."

Xu said that it is easier to create realistic works than works like Universal Celebration that require creativity to design the contents.

But for amateurs and beginners, even realistic paper cuts can be difficult.

|

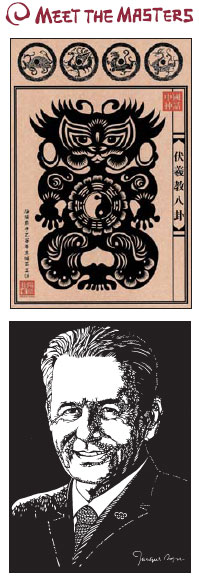

Top: One piece from Xu's Chinese legend series. Above: Portrait of Jacques Rogge cut by Xu. [Photo/provided to China Daily]

|

After sending the original pieces as gifts, Xu reproduced the two portraits and hung them in his workshop. Most visitors to his studio can not help talking about them, usually commenting that they are "as real as any picture or painting".

"And that is where the problem lies," Xu said. "If it's too real, it can be replaced by other forms of arts, such as photography and oil painting, and will lose the unparalleled fascination of being a piece of cut paper."

The public's other misunderstanding is thinking that only scissors are used to finish the works. Being a branch of traditional pierced art form, paper-cut actually requires both cutting and carving.

Originating 3,500 years ago during the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th century-11th century BC), pierced art was first applied on metal. The invention of paper during the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) has since then made the art more acceptable to ordinary people and paper cutting developed and thrived.

Born in Beijing, Xu spent 21 years in Anxian, a small county northeast of Chengdu in Sichuan province, where he was introduced to farm life and folk arts like walking on stilts. Xu said the people in the countryside helped inspire his lifelong devotion to the craft. He returned to Beijing in 1990 but did not start selling his works until 2003.

His yearly turnover has averaged about 200,000 yuan since 2005, although he made 400,000 yuan in 2007.

Xu is more than happy to see his work selling but he is clear about the differences between "works to meet demand" and "works to pursue real art".

"I think the two can run parallel," he said. "Paper pieces that feature lucky characters and small animals always sell best. Most people just don't see that the other pieces are more vivid, more traditional and more touching."

Although Xu's son has no plan to learn the craft, the master has already had several apprentices who have gone on to win international awards.

Xu said he has been considering taking his works to the auction market, with many showing an interest. "But it is still not the right time," he said. "Paper is too hard to preserve for a high price, and paper cutting is too easily pirated."