Memories of respect etched by culture

|

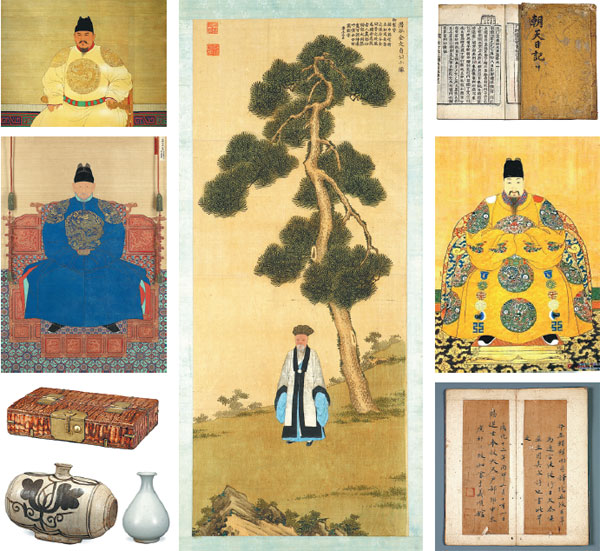

Clockwise from top left: Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of the Ming Dynasty; the portrait of Kim Yuk shows the senior Korean official standing under a giant pine tree; diary kept by Lee Heul, a Korean emissary to China who died in Beijing in 1630. The four big Chinese characters read chao tian ri ji, or Dairy of the Journey to the Heavenly Kingdom; Emperor Wanli of the Ming Dynasty; an example of literary diplomacy between Ming China and Joseon Korea-calligraphic works by Chinese and Korean emissaries; a white porcelain vase from 15th-16th century Korea; a porcelain pot from 15th-16th century Korea; a file case from Joseon Korea demonstrating the natural grain of wood; Yi Seong-gye (1335-1408), founder of the Korean Joseon Dynasty. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

Political careers

The political careers of many Korean emissaries, Kim and Nam included, straddled two Chinese feudal dynasties, those of the Ming and Qing.

"The transition was in no way smooth," says Fan, the history professor. "For years the Ming Empire was at war with the Manchu, a nomadic group from northern China that later conquered all of China and set up their own empire known as Qing. There was fierce debate at the Korean court as to which side to support. But one thing seemed clear: siding with Qing was a pragmatic decision and siding with Ming was a moral one. At one stage, Korean soldiers were fighting Manchu troops alongside the Ming army."

Yet when the dust settled, the Korean kings had no choice but to be practical. Korea was still a vassal state of China under Qing, but certain things changed.

"The once strong emotional, cultural and spiritual ties once between China and Korea became tenuous," Fan says. "The Manchu rulers, members of a culturally less-sophisticated ethnic minority group, did not engender in the Koreans the same sense of admiration as their Ming predecessors once had."

Envoys were still sent to Beijing by the Korean court, but under different names. Earlier they had been called chao tian shi, or emissaries to the heavenly kingdom; during the Qing era they were reduced to yan xing shi, meaning emissaries to Beijing.

Reflecting on the phenomenon, Fan says: "Zhu Yuanzhang, the founding emperor of Ming, called Korea bu zheng zhi guo, a country that his empire would never try to lay her hands on. It was a drastic change of policy from the one adopted by the Mongols, whose rule Zhu had helped end. Under Mongol rule, Korea was taken as a Chinese prefecture. No wonder kings of Korea were grateful toward Ming."

Invasion

Between 1592 and 1598 Japan under Toyotomi Hideyoshi invaded Korea. The Ming Emperor Wanli twice sent troops to Korea to counter the Japanese, in 1593 and then in 1597 respectively, when his empire was being attacked by Mongols from the west. While the war ended with the sudden death of Toyotomi in 1598, the military help, which many Korean kings believed to have saved Korea from demise, was not forgotten.

In a telling show of nostalgia, Korean files from the Qing era are often dated using the reign title of the last Ming emperor, Emperor Chongzhen.

The exhibition includes a diary kept by Lee Heul, a Korean emissary to China, between July 8, 1629 and June 8, 1630. In 1899 the diary was reprinted in Korea. In the epilogue, it is noted that the reprinting was made in the 272nd year of the reign of Emperor Chongzhen, 255 years after the last Ming emperor hanged himself on a tree in his royal garden.

"Yi Seong-gye started the Joseon Dynasty in 1392, 24 years after the founding of Ming," Fans says. "The first thing the Korean king did was to ask for recognition from Zhu the first emperor of Ming. The Joseon Dynasty came to an end in 1910, one year after the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1911. Both endings signaled the end of both countries' dynastic history. And both were to be followed by a chaotic, bloodstained era filled with struggles for personal freedom and national independence.

Lee died in Beijing on June 9, 1630 - one day after he finished writing his diary.

"In those days to be an emissary was not completely without risk," Ni says. "Nature could jeopardize the journey. Or, one could get seriously ill and die in a foreign land. But Lee, like most of his fellow emissaries to China, left behind writings that, together with other records, shed light on a shared memory in the two countries' history."