Keys to stability

Ensuring peace in Southeast Asia through the upholding of the ZOPFAN Declaration

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations, having pronounced its centrality in addressing regional security concerns and development priorities, remains steadfast in observing its non-aligned commitment amid the Sino-US geopolitical face-off.

This reminds the world of its consistency in endeavoring to make the region a zone of peace, freedom and neutrality (ZOPFAN), as was underscored by the ZOPFAN Declaration inked in Kuala Lumpur in 1971.

The signatory parties, comprising the then foreign ministers of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and the special envoy of the National Executive Council of Thailand, publicly stated their intent to keep Southeast Asia "free from any form or manner of interference by outside powers" and "broaden the areas of cooperation".It stood as a bold and defiant move against the prevailing tide of rallying behind the United States-led West when the specter of a "domino effect" was riding high across the region. The overture to Beijing by Kuala Lumpur that culminated in the fostering of bilateral ties between Malaysia and China set in motion the momentum of engaging with China for the entire bloc in its collective pursuit of peace and coexistence. It marked a bold shift toward equidistant diplomacy by ASEAN during the Cold War years of ideological confrontation.

It is this tradition of non-alignment that underpins the much-touted ASEAN centrality. The concept, first brought to light in the ASEAN Charter in 2008, underscores the notion that ASEAN should be the "primary driving force" in shaping the bloc's external relations and multilateral cooperation in an open, transparent and inclusive regional architecture.

ASEAN's role in creating development opportunities through trade and investment ties with its regional partners, including China, has been impressive. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, endeavored by ASEAN, stands out as a monumental achievement of inclusive multilateral economic cooperation that helped break the gridlock in the fostering of a much-awaited trilateral free trade agreement between China, Japan and the Republic of Korea. Three years on, the 15-signatory mega pact looks set to catalyze further the regional economic integration across the region amid rising economic protectionism and fragmentation.

Meanwhile, the various dialogue fora initiated by ASEAN, namely the ASEAN+3 (the 10 ASEAN member states plus China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea), ASEAN Regional Forum, and the East Asia Summit continue to manifest ASEAN's relevance and capacity in managing and addressing the rising risks and security concerns across the region.

While ASEAN centrality has been greeted with broad political buy-in by both the US and China, alongside the European Union, the ASEAN-skeptics notably political pundits in the West, never cease to cast aspersions upon the effectiveness of ASEAN centrality in addressing the protracted South China Sea maritime disputes.

Time and again, the outstanding disputes on overlapping maritime territorial claims in the South China Sea are cited to prove the point. The inconclusive Code of Conduct in the South China Sea is in the cross-hairs of the hostile Western narratives that dismiss the protracted negotiations as chelonian, and ASEAN centrality as nothing more than mere rhetoric.

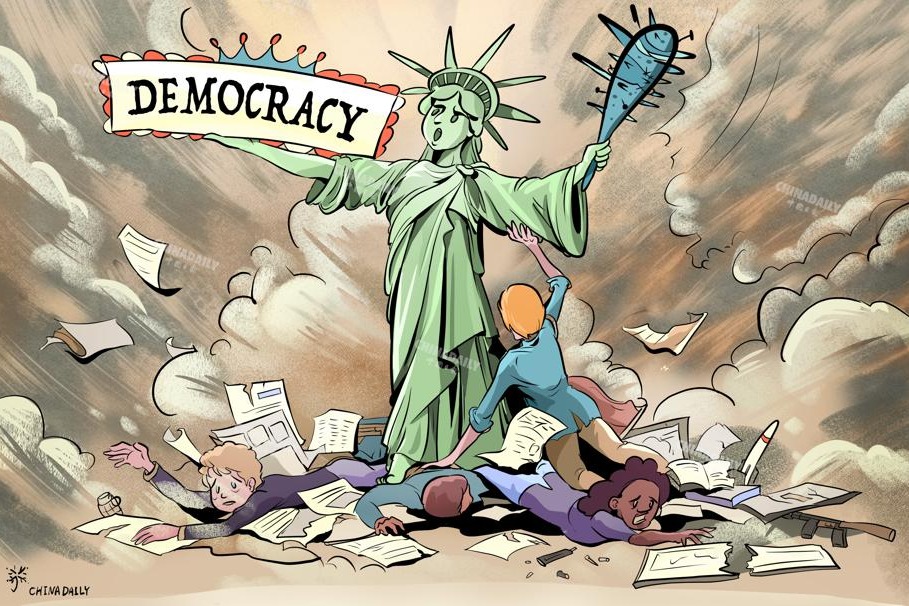

The venting of frustration by President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. of the Philippines over the purported inaction of ASEAN to the standoff between vessels of China and the Philippines in the disputed waters at the recent ASEAN summit in Laos, was widely seen as a brazen move to put ASEAN cohesiveness and centrality to the test. Prior to the summit, the international media controlled by the West had been earnestly instigating ASEAN to take issue with its top trading partner, China, over the standoff in the name of solidarity. When the outcome turned out otherwise, ASEAN centrality was made the immediate target of scorn by the West.

Yet, intriguingly, both their state actors and the media seem to have coincidentally turned a blind eye to the fact that Manila has in the first place reneged on its decades-old commitment to ASEAN's ZOPFAN Declaration when it gave the US the liberty to meddle with the territorial row between China and the Philippines.

From the Western perspective, there has been a stereotype impression that Southeast Asia needs the US military presence, if not the existence of its military bases, in the face of Chinese growing assertiveness on its territorial claims on the South China Sea. The logic of troop deployment by the US in Southeast Asia purportedly to thwart the possible influence of China is no different from that of collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty signed in 1954 in Manila, at the height of Cold War ideological confrontation.

In retrospect, the demise of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization in 1977 following its dissipation of traction is in itself a clear proof that the Western-inspired military deterrence has never been a viable option to address regional security concerns. Instead, it has proved that the peace dividends accrued from inclusive engagement and peaceful coexistence provide a conducive environment to development that brings about common prosperity benefiting the region. This development-driven security model provides a viable option in the contemporary context, notably in Southeast Asia where pursuit of peace and stability is the common agenda.

Against the present scenario of economic fragmentation and political distrust, the timely emergence of the Belt and Road Initiative followed by the Global Development Initiative and the Global Security Initiative presents a refreshing hope to reset the ailing global order.

Being the initiator of such ground-breaking initiatives, China, alongside ASEAN, its top trading partner since 2020, has presented to the world a successful template of multilateral cooperation through economic integration in the ASEAN-China FTA and the RCEP.This bodes well for development-driven security collaboration between the two parties representing a total population of over 2 billion, so long as their existing disputes are allowed to be resolved through positive engagement without the interference of non-stakeholders from outside the region.

Alongside this, ASEAN should also be watchful to not slide into triumph-induced complacency. Indeed, it was no small feat for ASEAN — a subregional grouping made up of small and middle powers of diverse cultures — to evolve from the modest goal of managing security challenges to claiming an undisputed spot at the center of the regional multilateral architecture after the end of Cold War.

Knowing that ASEAN will not be spared from the major powers' rivalry, the 10-member bloc must therefore uphold its autonomous strategic diplomacy at all times. In this context, the ZOPFAN principle remains relevant in the collective interest of preserving peace and stability across the region. No single member state should ever be allowed to defy the spirit of ZOPFAN Declaration merely to serve the narrow interests of its state actor.

The author is president of the Belt and Road Initiative Caucus for Asia Pacific (BRICAP). The author contributed this article to China Watch, a think tank powered by China Daily. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

Contact the editor at [email protected].