Macao is not like Hong Kong

Editor's note: Tom Fowdy graduated from Oxford University's China Studies Program and majored in politics at Durham University. He writes about international relations focusing on China and the Democratic People's Republic of Korea. The article reflects the author's opinions and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

This week commemorates 20 years since Macao's return to the motherland, marking China's second Special Administrative Region (SAR) alongside Hong Kong. Unlike its neighbor, Macao is not in a status of chaos, unrest and violence. Instead, it is proving to be an immensely successful hub and its role as a financial center in comparison to the decline of its fellow SAR is likely to increase over time.

As a result, Western journalists and commentators responded to the event with sour grapes and cynical coverage, implying that Macao was not choosing "its best interests" because it had not chosen the path of Hong Kong. The pro-Hong Kong journalist Jeffie Lam shrugged "so much for Macao people ruling Macao" accusing Beijing of "sending mainlanders to Portugal" to "groom an elite" for the city. Associated Free Press journalist Jerome Taylor moved to accuse the city of "deference to authoritarian rule".

These reactions reveal an inset ideological bias within coverage of China related matters, resting on the assumption that no actor, be it an individual, city or country can legitimately "choose" allegiance with the country and instead, it is their "true interest" to rebel against it and be in a perpetual state of disorder like Hong Kong, despite whatever costs it imposes. Therefore, anyone who does otherwise is merely "controlled" or "subordinated." Again, there is also the underlying assumption in such coverage that Macao does not "truly belong to China".

However, Macao is not like Hong Kong. It does not boast an exceptionalist identity with an inflated sense of status and self-importance, therefore neither does it wield the persecution mentality which residents of its neighbor does. Thus, Macao residents are at large comfortable enough to come to terms with their existence as part of China.

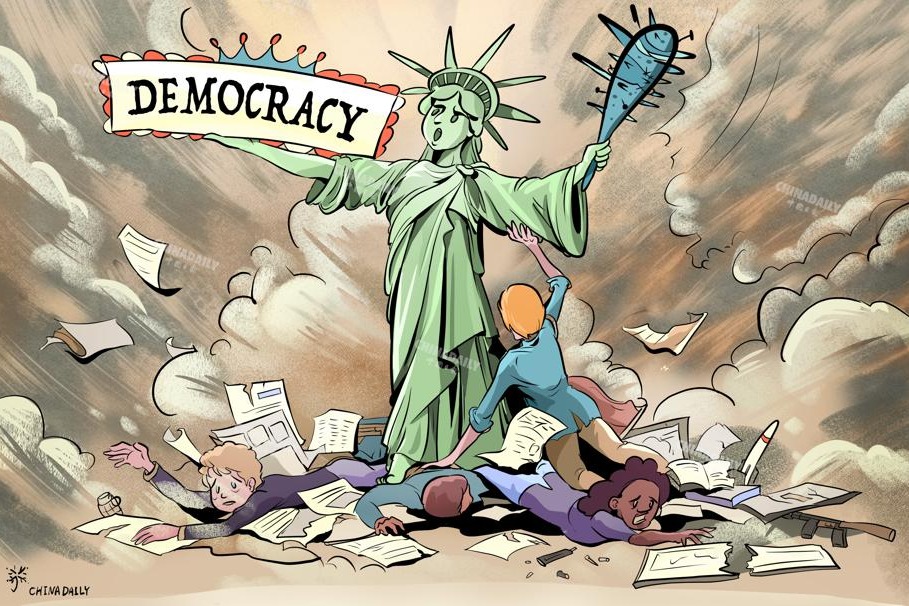

Liberal political thought assumes that there is one, universal and indisputable "political truth" in the world which through "enlightenment" all individuals will adhere to. That is, all people will naturally yearn for Western style liberal-democracy and any other political system is inauthentic and illegitimate, preventing their populations from receiving this "truth" by deception.

On this ontology, liberal commentary assumes that it is impossible for one to authentically identify or support a differing political system. They must either be "brainwashed"or "corrupted" into doing so through material incentives, as liberal democracy is the only "true" and "correct" view.

These ideological biases constrain the Western view of China accordingly; with all Chinese views accept ones which suit the narrative routinely dismissed as illegitimate. In turn, this has shaped the dichotomy of coverage concerning Hong Kong and Macao.

Protesters in Hong Kong are praised as being enlightened, progressive and commendable despite their violent tendencies; Macao, for "not rebelling", is now argued to be a product of Chinese domination, greed and thus refuses to act in its own "true interests" – as if there is only "one way" it can legitimately be.

However, Macao is not Hong Kong and making this distinction is a misleading equivalent. The differences between the two are not because of "China" but because of historical circumstances.

Hong Kong is the way it is because it was a British colony of paramount importance in the 20th century which as a result developed an exceptionalist identity, deeming itself to be "better" than the rest of the country, which is at the root of their exaggerated persecution complex today. Macao, on the other hand, is smaller and was of less historical importance, therefore when Chinese populated the territory as refugees during the War of Liberation they did not develop an antagonistic, separate identity.

Portugal also acknowledged the territory was Chinese in a more pragmatic way than Britain did and at an earlier point, even though the handover came after. As a result of these circumstances, Macao residents are less inhibited to be antagonistic towards the Chinese mainland and can accept their belonging as part of the country, whereas the people in Hong Kong cannot.

Therefore, as a whole, the argument China has successfully "controlled" one territory but not another, is misleading and simplistic. The ideologically inclined argument that Macao's true interest can only lie in mimicking the violence, chaos and destruction in Hong Kong is patronizing and condescending.

Liberal political thought fails to account as to how differing identities can produce different outcomes accordingly, and thus the reality is that divergent historical experiences have shaped Hong Kong and Macao in distinct ways. One city is able to comfortably come to terms with its existence as part of China, the other is not, that does not mean foul play is involved.